Fifty years after his death, Pier Paolo Pasolini continues to challenge European culture: his warnings about power, the media, and identity resonate today with disturbing relevance.

By Jorge Alonso Curiel

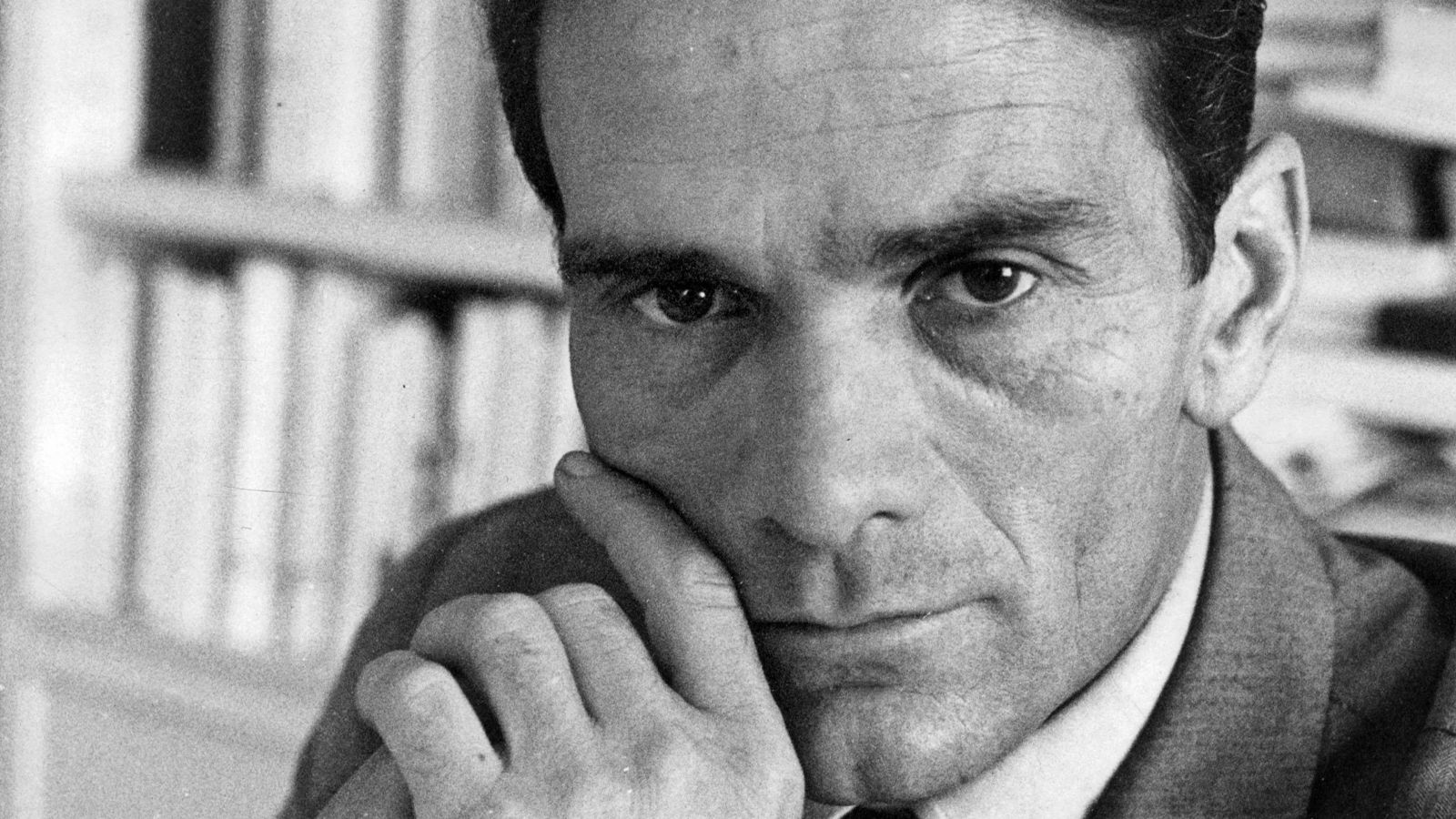

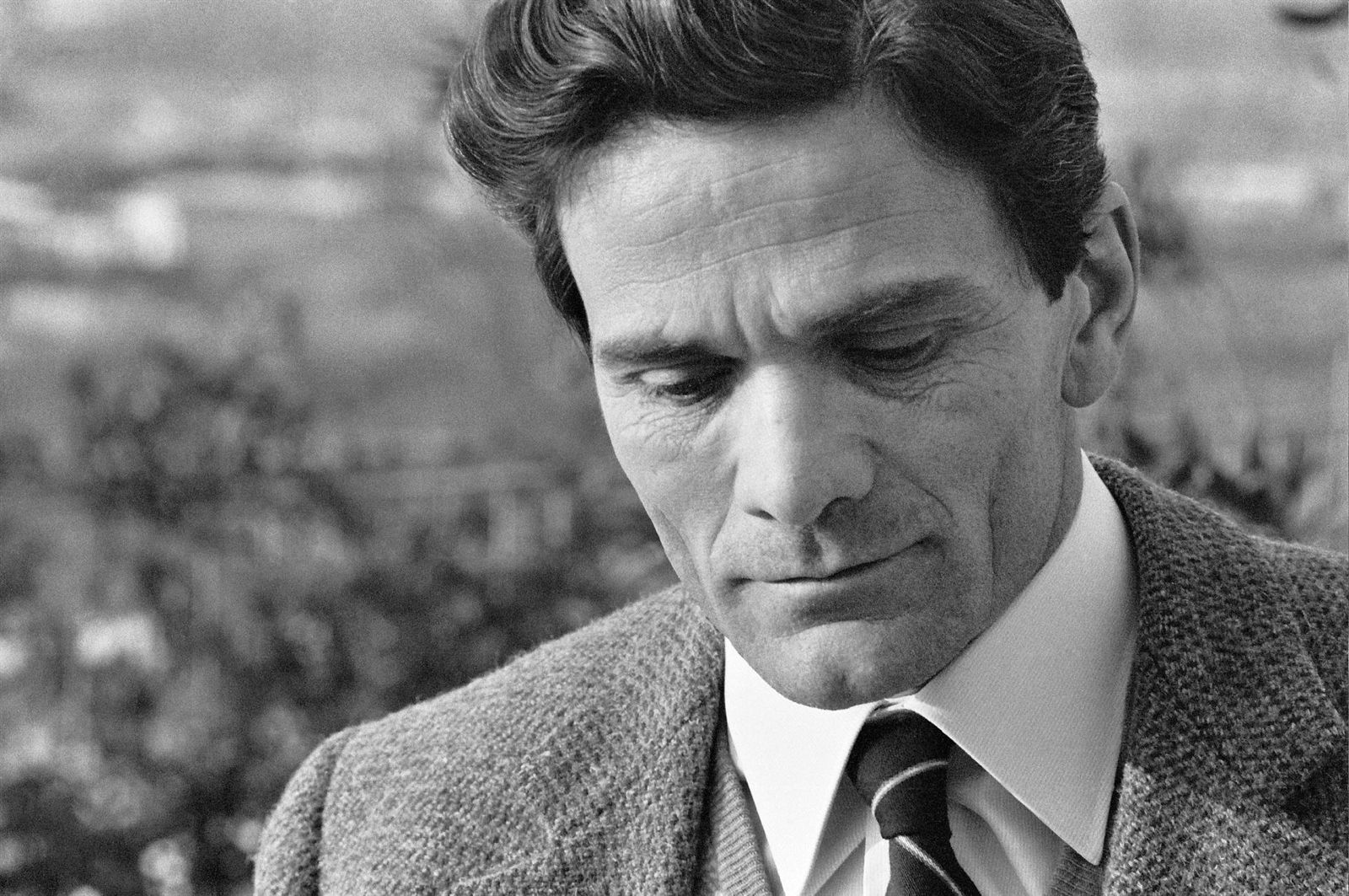

HoyLunes — Fifty years after the mysterious death of Pier Paolo Pasolini (Santo Stefano, Italy, 1922), whose body, in extreme conditions, was found on November 2, 1975, in a vacant lot near Ostia beach, barely 30 kilometers from Rome, the world once again turns its gaze to the most uncomfortable, free, and controversial intellectual—one who left no one indifferent—in recent Italian history. The anniversary arrives accompanied by cinematic retrospectives, critical reissues, and public debates that seem to reopen old questions about his work, his thought, and the violent and still unresolved circumstances of his death.

Pasolini — poet, painter, novelist, screenwriter, film director, and polemical columnist — left behind an extensive body of work ranging from tales of Rome’s suburbs to visionary essays on the rise of consumerism.

But he also left behind a political and cultural void: that of an intellectual who chose direct criticism, even against his own communist allies. His first novels, Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta, scandalized Italy during its economic miracle for their raw depiction of the youths from Rome’s slums. In cinema, after collaborating as a screenwriter on more than a dozen productions, he built as a director a filmography marked by a distinctive style that spans from the brutal neorealism of Accattone, his debut released in 1961, to the attack on Christian morality and Christianity in Teorema (1968), and the shocking, sacrilegious, and extreme display of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, released in 1975, just weeks after his tragic death.

Discomfort as an Editorial Line

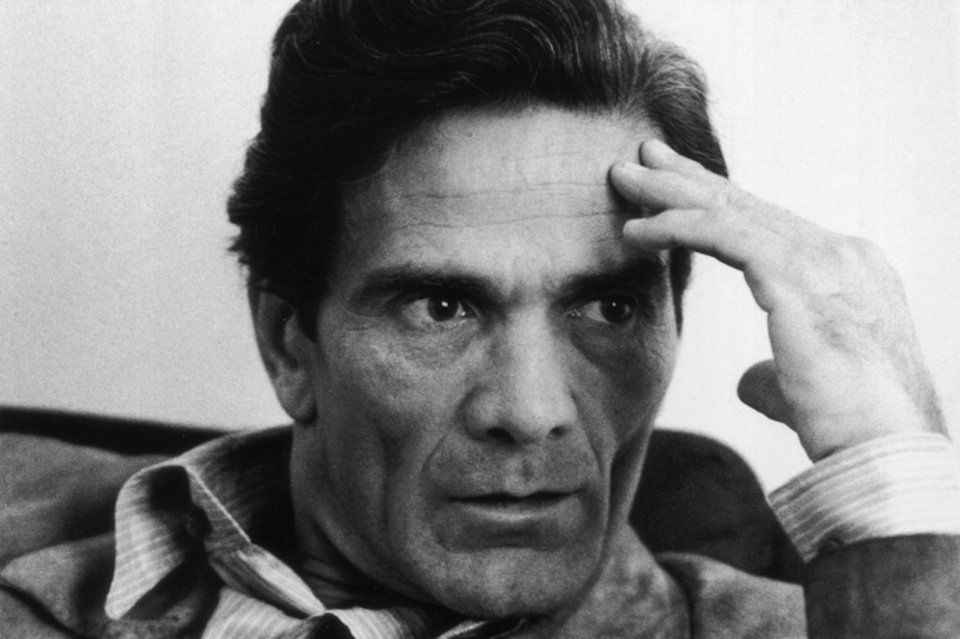

Pasolini’s public figure was as influential as his artistic work. His newspaper and magazine articles discussed the rapid transformation of Italian society with a mix of alarm and insight: he denounced the loss of popular cultures, the linguistic standardization imposed by television, and the “anthropological mutation” brought about by mass consumption. His discourse, uncomfortable for every political force, placed him in an unusual position: that of an intellectual who did not seek followers, but to provoke questions.

His analysis of the media — which he saw as the new center of power — resonates with particular force in today’s Italy, marked by debates about disinformation, polarization, and media concentration. Many of his texts, written more than half a century ago, circulate on social networks today as if they were recent diagnoses.

On this anniversary, various Italian cities are organizing tributes, but the memory of Pasolini is not confined to the cultural sphere. His murder remains an open wound, with investigations and theories that periodically resurface.

For many, he was not only the victim of a crime but also of the very social and political tensions that he tirelessly denounced.

Half a century after his death, Pasolini remains a key author in public debate because he offers no comforting answers. His work compels us to look directly at what society would rather ignore: persistent inequality, the transformative — and sometimes devastating — power of the media, and the fragility of collective identities in an increasingly uniform world. Remembering him today is not a ceremonial gesture; it is an act of intellectual resistance — and also an opportunity to discover, or rediscover, the literary and cinematic work of one of the essential figures of European culture in the second half of the 20th century.