A mother, a stranger, and a soup tureen: the invisible border between fear and hope.

By Nuria Ruiz Fdez.

HoyLunes – The young man stopped at the doorway, shoulders hunched, as if crossing that threshold might hurl him into an unknown abyss.

Are you Lucía’s mother? he asked softly from the doorway.

Margarita eyed him with suspicion: that exotic, youthful yet troubled face did not immediately inspire trust. Even so, her mother’s instinct told her to listen.

I am. Who are you?

My name is Youssef. I’m a friend of your daughter.

Do you know where she is? Tell me— Her voice rose into the immensity of the night.

May I come in?

Yes… come in, let’s go to the kitchen, we’ll be more comfortable there. But tell me, do you know anything? Please, talk to me… Has something happened to her? Why are you here?” The questions tumbled out of her mouth, tripping over one another.

They sat around the table. The crescent moon slipped through the window like another guest, flooding the room with its vast, pale presence.

I don’t want to alarm you, but I haven’t heard from her in three days. People in town said you were also looking for her. I was supposed to meet your daughter that night to go to the fair in La Línea. She was to meet me there… but she never came. His voice faltered. “I called her phone until it stopped ringing, spoke to her friends, and no one had seen her. That’s why I’m here.

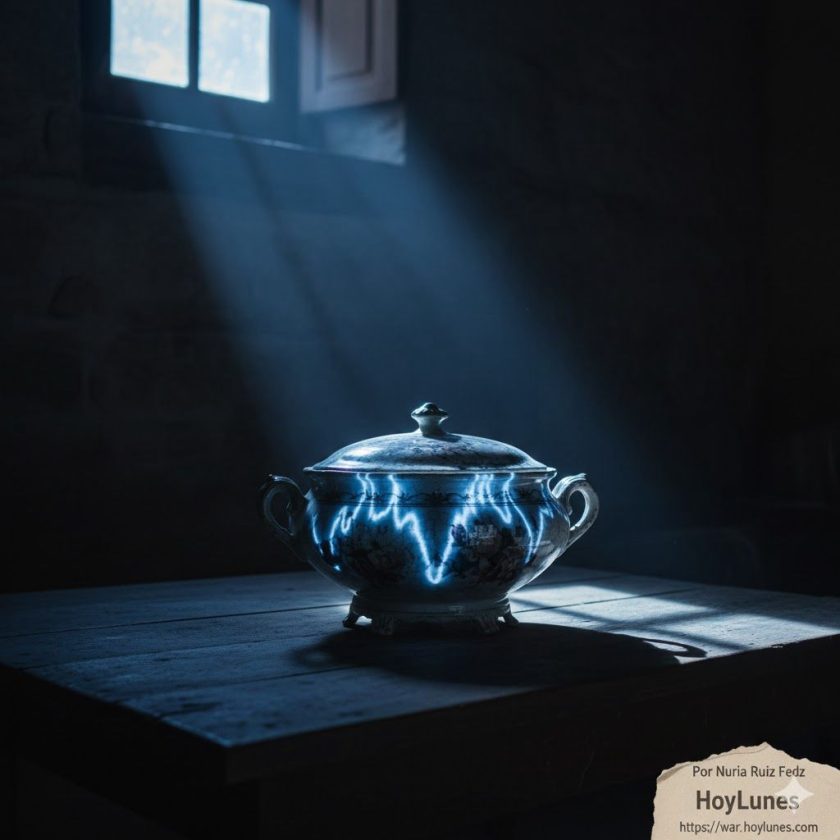

Margarita’s heart skipped. She reached out a trembling hand to touch the tureen’s cold porcelain, as if it might calm her. Without another word, she took a ladle and served some broth into a bowl, offering it to him. Serving it felt like invoking her dead—those women who had always found in the kitchen a way to speak of pain. Somewhere in the house, a cricket sang rhythmically in the dark.

Margarita watched as he sipped the soup with quiet respect. Steam fogged his lashes. When Youssef took the first spoonful, his caramel-colored eyes brightened—pure, clear—and melted her distrust.

Where are you from? You speak Spanish very well…

The young man smiled shyly.

I’m from Tangier, ma’am. But I’ve lived in Algeciras since I was six. My parents crossed the Strait looking for work, and I grew up here.

Margarita arched a brow, studying him like someone testing the ground before stepping forward.

And how did you meet my daughter?

Youssef lowered his gaze to the bowl, stirring the broth.

At the Institute. We were classmates, both studying to become nursing assistants.

She has… that way about her… that makes you trust her. I feel so at ease when I’m with her. She used to tell me about her hometown in León—its fields, its cobblestone streets—and I told her stories about my city, Tangier, how the sea there smells of spices. That’s how we became friends. Very close friends.”

A glint crossed Margarita’s eyes—a mix of surprise and restrained tenderness.

Lucía never mentioned you.

I know, Youssef nodded. “She said you had too many worries, that you didn’t understand her, that this town suffocated her. But believe me, ma’am, I only want to find her.”

The tureen, still on the table, seemed to listen.

“I don’t understand any of this,” she murmured as he drank. “Lucía left a letter, but… it doesn’t seem to be written by her hand. She took it from her pocket and showed it to him.

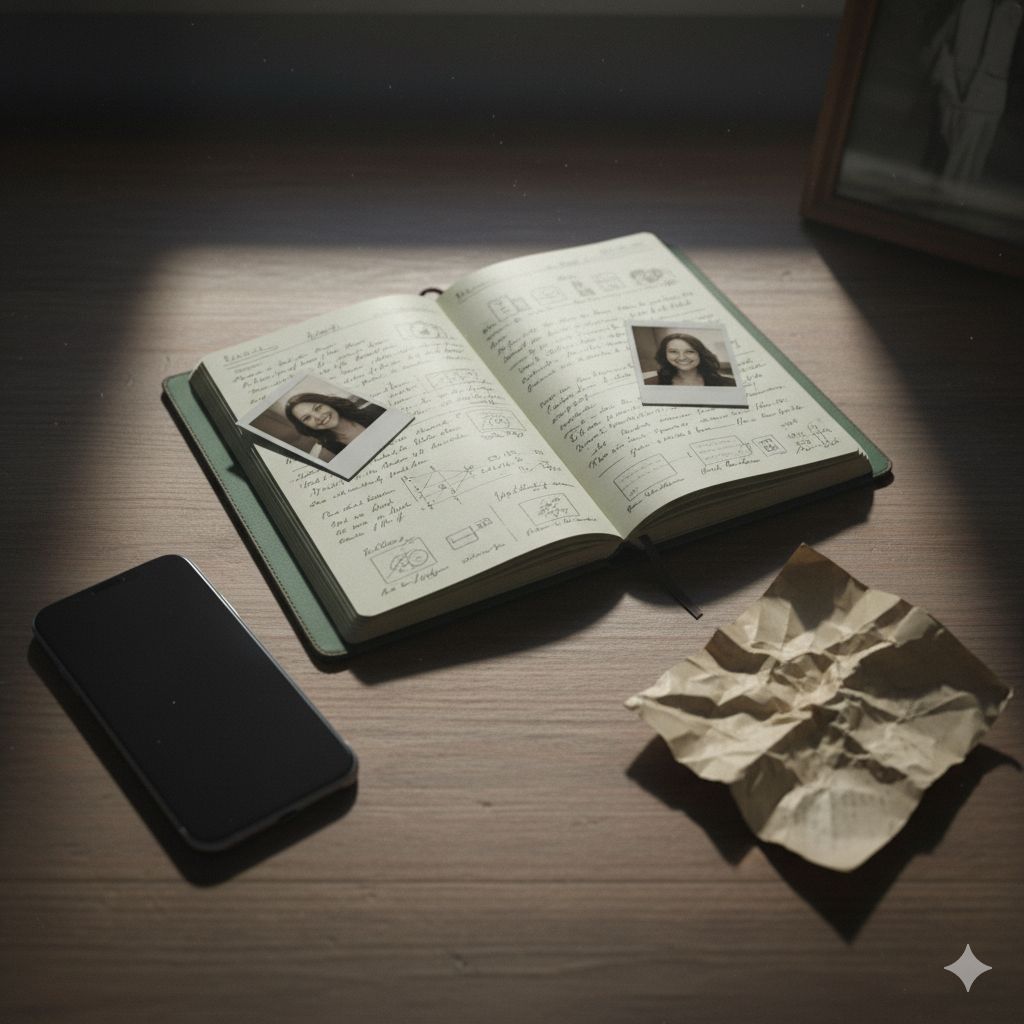

Right. Youssef touched it, as if his fingers might extract answers. “Her handwriting is big and round—I know because sometimes we write songs together, and she keeps them in a hard-covered green notebook, with her initials written in marker. Did she take it? She would never leave it behind. If she did… then she didn’t leave of her own free will. That, I can assure you, the young man said firmly. “We have to find her.

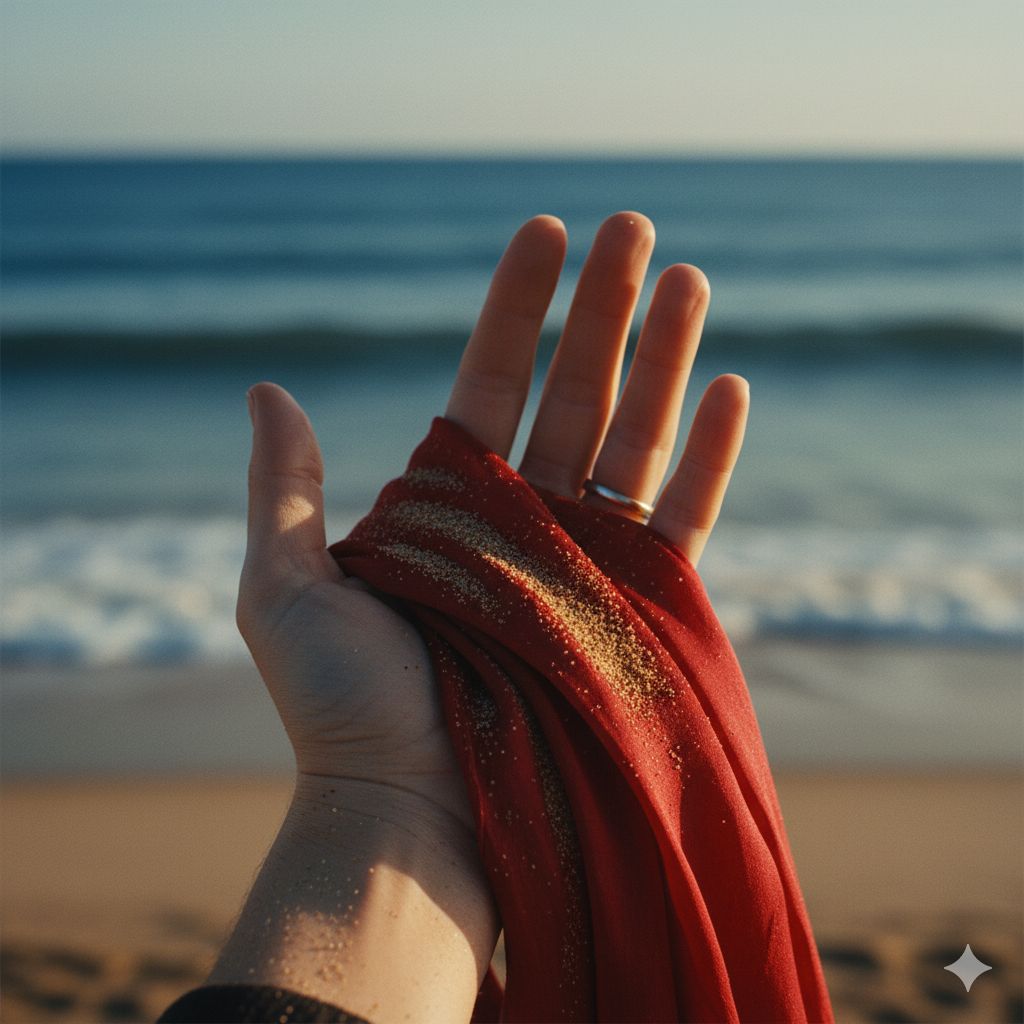

I looked in her room; everything’s untouched. That notebook you mentioned is on her desk next to her phone. When I came back from searching for her, the phone was already off, out of battery, and I don’t have the code to open it. Only some clothes and her ID are missing. She didn’t take any money or the notebook. And this red scarf—I found it buried in the sand, as if someone had stomped it down.” She showed it for a moment, then put it away again, as if afraid he might take it.

Have you gone to the police?

Yes, the morning after she disappeared. A policeman took notes half-heartedly, as if it were just another case. He told me she was probably with friends—‘the fair’s a big fair,’ he said, twirling his pen, barely looking at me. Later another officer said they’d activate the search protocol, but I don’t trust them, Youssef. No one has called me yet.

You have to go back; it’s been three days. Maybe they’ve found something. I’ll go with you if you want.

You’re right. Tomorrow I’ll go back,” she said with resolve. “I have to know if they’ve learned anything.

And so they did. Youssef promised to pick her up the next morning before ten. That morning, he waited outside her door, restless, hands deep in his pockets.

He parked near Avenida España. They left the car and walked quickly, silent and tense. When they saw the police station, she moved ahead; he held her arm.

You should go in alone, he said quietly. It’s better that way.

Why? Margarita looked at him, surprised, almost offended.

He met her gaze for an instant, then looked away. Because sometimes my name and my skin are enough to raise suspicion. Believe me, I know.

Margarita listened, not fully understanding. She had never known that kind of mistrust, that suspicion that clings to other people’s skin. She had never imagined that simply being called Youssef could be a burden.

I don’t understand, she murmured, almost like a child’s protest.

He didn’t move, only nodded slightly—firmly, like someone who has learned that lesson too many times. Margarita hesitated, then finally went in alone, just as before.

She left him standing across the street, distraught, and entered the building. The reception smelled of stale coffee and damp paper. Behind the counter, the same older officer from before greeted her.

Are you sure she didn’t take her phone? he asked absently, shuffling papers. And the note—you’re sure she didn’t write it?

Yes, she replied, leaving no room for argument.

Then a young female officer, her uniform freshly pressed, appeared in the doorway.

Mrs. Lafuente, I was just about to call you this afternoon, the officer said. We have some information that may be relevant: there are signs your daughter was seen crossing the border into Gibraltar with a man. The border cameras provided us this image.

Do you recognize this man?

She showed her a black-and-white photo—a screen capture. In it, her daughter appeared with a man beside her, shown in profile. His hair was shaved at the sides, almost white-blond. On his bare shoulder, under a white shirt, a shadowy tattoo could be seen—a row of numbers, hard to read. He was gripping her by the arm, while Lucía seemed to pull away, her body leaning backward, resisting.

No, I don’t know him. Have you gone to look for her? she asked in a trembling voice.

We can’t operate inside Gibraltar. Enma, the young officer, shook her head. “The jurisdiction of the National Police and the Civil Guard ends at the border; within the Rock it’s the Royal Gibraltar Police who must act. But we are sharing information and coordinating with them. We won’t leave you alone in this. We’ve activated the protocols and opened channels of communication.” She placed a hand gently on Margarita’s shoulder.

Outside, Youssef waited, lighting one cigarette after another with unsteady hands.

When Margarita came out, he rushed to meet her as if his life depended on it. She told him, calmly but distrustfully, what the officer had said and how little she believed in the police’s efficiency. He listened, eyes fixed, then said thoughtfully:

I have a friend in Gibraltar. If you want, tomorrow we can go there. He can help us.

Margarita clutched Lucía’s red scarf in her pocket. For the first time since her daughter’s disappearance, she felt that someone was truly willing to walk beside her—all the way—to find her.

Yes, tomorrow we’ll cross the border, she replied.

To be continued…

#hoylunes, #nuria_ruiz_fdez,